In the Neurology Department at Allegheny General Hospital’s Hemlock Building, Abigail Bailey’s body folded forward in her chair.

Her muscles tightened as if someone had forced the air from her lungs.

Her nose burned, her chest hitched and she gripped the chair’s armrests to keep from collapsing.

Abigail’s younger sister reached out and gently brushed a section of hair from her face.

“I felt it kick in,” Abigail said. It was her physical reaction to her brain wirelessly connecting to the laptop sitting on the examination bed next to her Friday.

Abigail, 24, of Hookstown in Beaver County, has lived and struggled with Tourette syndrome for more than two decades. But it wasn’t until last year — when a bladder infection led to sepsis and triggered a spike in painful motor and vocal tics — that she chose to pursue an experimental treatment.

In March, she underwent a two-part deep-brain stimulation procedure. Surgeons implanted a device that delivers electrical impulses to targeted areas of the brain to treat motor disorders.

“I was like, ‘It’s time. I don’t even care what it takes. I just want my life back. I want to be happy,’” Abigail said, remembering the constant physical pain her uncontrolled tics put her through.

Now, eight months later, she is working full-time, living independently and preparing for her 2026 wedding.

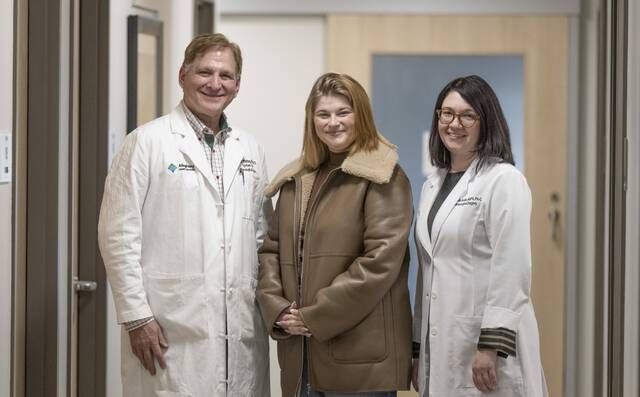

Spirits were high Friday as Abigail, joined by her sister Emily Bailey and her mother Colleen Bailey, visited the Allegheny Health Network hospital in Pittsburgh’s North Side. It was a routine visit to recalibrate the electrodes in her brain to help minimize the involuntary movements associated with Tourette syndrome.

Neurosurgical Physician Assistant Amanda Webb pointed to the different parts of Abigail’s brain they were targeting on the laptop’s screen. Everyone in the room was struck by the technology and shared memories of times when Abigail’s tics were less controlled.

Despite the nature of their visit, everyone in the hospital room laughed and told stories to the doctors and staff.

“If anybody in the world should’ve had Tourette, it was Abby — because she handled it like a pro,” said Colleen.

‘Not curable’

Abigail, who grew up on a farm in Hookstown, was 3 years old when her parents began to notice symptoms of Tourette syndrome.

Tourette’s is a neurological disorder marked by sudden, repetitive, uncontrollable movements and sounds, with symptoms typically beginning between ages 5 and 10, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

The condition can become dangerous when tics lead to accidental self-injury.

In Abigail’s case, she has broken several fingers and even her ribs during severe tic episodes.

She didn’t realize until middle school how disruptive her tics had become. By high school, she was attending a modified schooling program.

Her tics became an issue when she distracted her classmates and interrupted lessons.

“There were points in her life when she was younger, when she was like a fish flopping on the ground,” Colleen said.

“I started noticing the older I got the … worse it was getting,” Abigail said.

She began to feel she was reverting back to childhood as she lost control of her body.

Growing up, Abigail spent a week each year at a camp for people with Tourette’s and their families. There, she made friends with other kids who shared her condition and heard stories of the severe bullying many of them faced.

“It was eye opening,” said Emily, her sister.

While Abigail said she never faced bullying or cruelty from other students, many of her teachers didn’t understand her condition.

As Abigail entered elementary school, Colleen met with the school board to discuss Tourette’s. She distributed handmade guidebooks explaining the condition and how to respond to it.

“We did everything we could in order to learn about Tourette’s, because it was devastating for us to find out. But you know, your daughter has something that’s not curable, and as a mom, you want to solve everything, because that’s your job, and you can’t solve it. So you have to learn everything about it,” Colleen said.

Abigail graduated from Eastern Gateway Community College with a degree in social work, before attending Robert Morris University, in pursuit of a degree in health services administration.

‘Everything pretty much revolved around my tics’

In December 2024, Abigail called her mother. She was extremely sick and scared.

“She said, ‘Mom, I can’t get out of bed. I can’t do anything. I need your help,’ ” said Colleen, teary-eyed in the waiting room of the neurologist, before the Friday check-in appointment. “I didn’t know she had gotten that bad again. It was so bad she couldn’t do anything. It was horrible.”

At the time she became ill, Abigail was living on her own and working as a case manager at a pharmaceutical company, helping people with chronic illnesses access care and develop treatment plans.

While hospitalized with sepsis, Abigail’s tics worsened drastically. She was placed on multiple different medications that left her feeling unlike herself.

“She barely remembers that month,” Colleen said.

Three months later, Dr. Donald Whiting performed two surgeries — one to place the electrodes in her brain and a second to connect them to a pacemaker or “battery” inside Abigail’s chest.

“In the brain, there’s circuits that connect to different structures in the brain that help modulate that activity and make sure that everything is moving smoothly … so by putting an electrode into one of those two areas and adjusting the electricity, we regulate that relay center,” said Whiting, chair of Allegheny Health Network’s Neuroscience Institute.

Abigail is one of only a handful of patients Whiting has performed deep-brain stimulation surgery on for Tourette’s. The Bailey family came across Whiting while researching the treatment when Abigail was still in high school, but it wasn’t until she got sick that they decided to go through with it.

“She was so scared, as a high schooler, of somebody operating on her brain,” Colleen said. “We researched Dr. Whiting, and we knew he was the best in the field. He’d been doing it for 20 years.”

While the device is approved by the Food and Drug Administration, insurance companies don’t always approve it because it is still considered experimental for Tourette syndrome, Whiting said.

Luckily, Abigail’s insurance covered the procedure. With the machine’s help, which runs 24 hours a day, she is able to live her life again.

“This is more personal, but the coolest thing in this job is to really be able to make a difference in people’s lives, and particularly young people like her. This is really just amazing that she’s now going to have a life, to get married and live in a house, get a job.” Whiting said. “To me, that’s just what it’s all about.”

Abigail has been engaged to her high school sweetheart, Shane Smith, since June 2024. In August 2025, she started a new job as a patient service representative for Heritage Valley Health System. Planning for the 2026 wedding is well underway.

“Everything pretty much revolved around my tics,” Abigail said. “You just have to get through it. … There’s life at the end of the tunnel, we (people with Tourette’s) just have to make it there.”